(Bookmark gifted by a 3-year-old grandson who generously shared his truck stickers.)

November 4, 2023

When leaves dance across the walkway and autumn’s chill is in the air, I like to take out an old copy of Washington Irving’s Sleepy Hollow to get in the mood for Halloween.

This small-format book exhibits the usual signs of wear. The fore edge is darkened by dust and age. The Copyright page is torn out, so I can’t date it exactly, but the publisher – The Platt & Peck Co. in New York – I’ve learned, operated from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. There’s a color plate of the main character, schoolmaster Ichabod Crane, in the beginning on the inside left with the same image replicated on the cover. There is nothing on the back.

The pages are intact, though slightly yellowed, displaying justified handset type, slightly askew occasionally as they pull into the binding. There’s charm in that. The paper stock is weighty and offers a tactile reward. There are lovely, wide margins, relaxing on the eyes, making for a quick, easy read, reminding me that consumable content is important. Interestingly, there is no writing on the spine so perhaps this book was never intended for a library shelf.

But I digress. I’m here to talk about the story – a tale so simple, it’s child-like, but as with many classics, can be enjoyed by adults who read between the lines.

This is not a monumental literary work but rather, a dutiful account of life in Colonial America, in New York state along the Hudson River, during the years preceding 1815-1819 when it was written. It was originally published in installments as part of “The Sketch Book.”

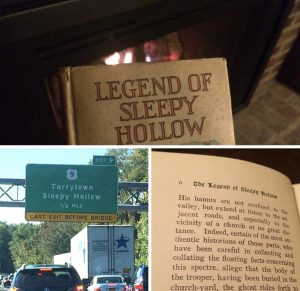

I’ve learned that Washington Irving spent time in Tarrytown, NY (where Sleepy Hollow is set; yes, there’s a real town by that name) in 1798, when he and his family escaped a Yellow Fever epidemic in New York City.

This experience supports the adage “write what you know,” because through his details, I can feel the forest, smell the earth, and see the expanse of water that is the river. (It doesn’t hurt that I grew up in the region and can attest to his accuracy.)

“The forests had put on their sober brown and yellow, while some trees of the tenderer kind had been nipped by the frost into brilliant dyes of orange, purple, and scarlet. Streaming files of wild ducks began to make their appearance high in the air.”… “On all sides he beheld vast store of apples; some hanging in oppressive opulence on the trees, some gathered into baskets and barrels for the markets, others heaped up in rich piles for the cider-press. Farther on, he beheld great fields of Indian corn, with its golden ears peeping from their leafy coverts, holding out the promise of cakes and hasty pudding.”

Some of the words and phrases are antiquated, but that’s all the more charming; the gist is clear. Irving paces his writing like a campfire tale, spoken in the slow voice of a dramatic storyteller. On occasion, he steps aside and refers to himself as the humble narrator. (I tried to emulate a similar style in Silver Line.) Irving’s role is not to interpret the plot but to relay it in the context of the times – in an era rife with New World mystery and superstition among the old Dutch families who inhabited the area.

Irving captures this uneasiness by telling of legends that lurk in the idyllic countryside. He notes the Hollow is near the place where British Spy, John Andre, was hanged and where a Hessian soldier, around Halloween of 1776, had been decapitated during the Battle of White Plains. (This, per a New York Historical Society account, October 25, 2013).

Like all good characters, Ichabod is flawed. He’s a man prone to indulgences despite his persona of a lanky, austere teacher (or ‘pedagogue’ as Irving calls him). Fact is, Crane covets the affluent lifestyle enjoyed by his love interest, the pretty and plump Katrina Van Tassel. Ichabod’s weakness for food is revealed as he craves the pies, meats, and rich dumplings offered at the Van Tassel home – an estate he might well inherit if he were to wed the fair Katrina.

Of course, there’s an antagonist, the large, arrogant Dutchman, Brom Bones, who vies for the attention of the wealthy damsel. He torments Ichabod, and we immediately dislike the bully because that behavior is still relevant today.

Poor Ichabod. In a single night, he is jilted by his love interest and forced to ride through the darkest recesses of the forest, places where hauntings have occurred and might again, only to encounter a towering menace on a black steed – the headless horsemen of whom he has heard so much.

Here’s where Irving does something right, reminding us (writers) about the importance of foreboding, flash forwards, and making the reader feel smart. When Ichabod can’t be found after his night of terror, only his saddle and a smashed pumpkin remain. Irving never explains why the pumpkin is there but lets the reader connect the dots to the “head” that was carried.

I think I particularly enjoyed re-reading this little story (a few pages at a time, over morning coffee) because it did not try to be more than it was. Authenticity is a good goal for people who play with words.